[ad_1]

Photojournalist Graeme Green went to Rwanda to document the recently opened Ellen DeGeneres Campus of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund and spend time with our nearest genetic cousins. He also witnessed a ray of hope on the horizon

‘They’re coming to us,’ said Emmanuel Ahishakiye, his voice a whisper.

This was surprising news. We were geared up and psyched to climb the steep, forested slopes of Sabyinyo volcano to find mountain gorillas, a trek that might have lasted anywhere between 30 minutes and a couple of hours. But, just a few minutes into the forest, the gorillas were saving us all the trouble. ‘The gorillas are always moving, always searching for food,’ explained Emmanuel, the manager of Virunga Lodge.

We heard them before we saw them, the sound of snapping branches announcing their arrival. I spotted a female among the bushes, and an infant, both obscured by leaves.

And then the rest emerged, one by one, sauntering along the trail, occasionally stopping to eat and to let the others catch up. On their backs, mothers carried babies, who eyed us curiously as they rode past.

The mighty silverback of the Muhoza family was a quiet, powerful presence among them. ‘This is Marambo, one of my favourite gorillas,’ Emmanuel told me. ‘This is one of the top five largest silverbacks in Volcanoes National Park. He’s big and handsome. Some silverbacks are aggressive and grunt at you to move, but he’s very humble.’

Giant that he was, the mighty silverback continued through the trees, paying us little attention. We were merely visitors; this was his domain, his forest. Marambo’s group numbered 18 gorillas, including eight adult females. ‘He’s a busy man,’ Emmanuel laughed. ‘We have six babies here. The youngest is four months old. This silverback was young and strong, so he took nine females. Before that, he did a lot of cheating and illegal mating. But he convinced three females to join him and his group grew from there.’

American conservationist Dian Fossey feared mountain gorillas would be extinct by the year 2000. But the Muhoza group is now just one among 23 gorilla families alive and well in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park.

Mountain gorilla numbers have steadily increased over the past 30 years. The most recent census, in 2015, showed 1 063 mountain gorillas, all found in the Virunga Massif and Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, spread across Rwanda, Uganda and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The International Union for Conservation of Nature recently updated the status of these gorillas from critically endangered to endangered, meaning the animal numbers are moving in the right direction.

That’s down to decades of work across the three countries by governments and conservationists, including Fossey, who helped to bring the gorillas’ plight to global attention.

A new campus dedicated to gorilla conservation was recently opened in Fossey’s name. I drove there from Kigali airport, winding steadily up into Rwanda’s green hills.

The Ellen DeGeneres Campus of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, just outside Volcanoes National Park, has taken two years and $15 million to build. ‘For many years, we wanted to have our own home, near the park, near the gorillas’ home, and near the communities we work with,’ Felix Ndagijimama, director of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund in Rwanda, explained at the entrance. ‘We’re in the heart of things here.’

I was given a tour of the facilities, including a research lab where a Rwandan field researcher is using a machine to test nutrients in forest plants that gorillas eat. Work is under way to study the DNA and genetic variability of the gorilla populations. Researchers at the campus also plan to look at how climate change is affecting gorilla habitat, including their food supply.

‘We are optimistic for the future, but it’s a delicate balance,’ said Veronica Vecellio, the Gorilla Program senior adviser. ‘That’s why it’s so important to be here. The gorilla is the only great ape that’s increasing in number. It’s a rare conservation story on this planet. People were the reason why gorillas reached the brink of extinction, and people are the only hope that they don’t go extinct.’

For those who do visit, the campus’s focus is the Conservation Gallery; its walls are filled with pictures of Rwandan conservation heroes, as well as animals that share the gorillas’ forest homes, from elephants to hornbills. Much of the exhibition space is dedicated to Fossey’s life story, including her work to gain the gorillas’ trust. She started out with basic equipment and a couple of tents, before setting up the Karisoke Research Centre between the volcanoes of Bisoke and Karisimbi. In 1985, she was murdered in her cabin, having been fighting against local poachers.

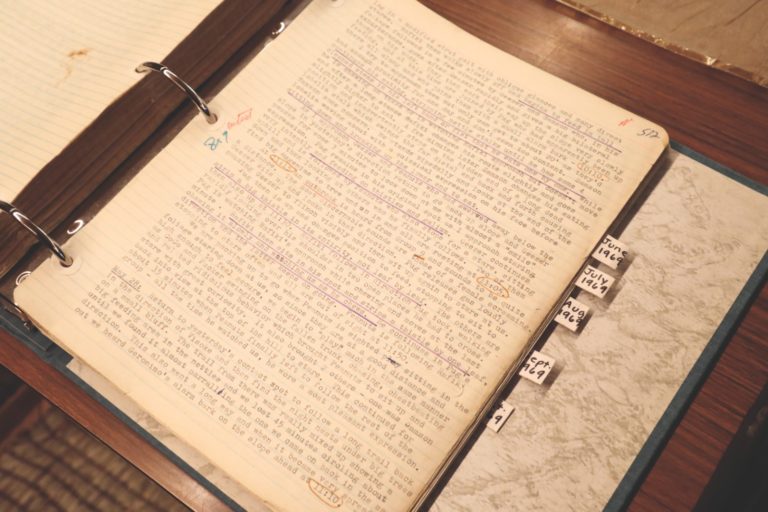

The notes on Dian Fossey’s recreated desk are originals – these field notes date from 1969 and were the basis of Gorillas in the Mist.

The exhibition space contains a recreation of Fossey’s Karisoke cabin. ‘This is pretty precious,’ Veronica told me, showing me a folder on the desk containing Fossey’s original typed field notes from 1969. ‘You have a sense of a person who was a pioneer in this work. She wrote everything. These notes were the basis for her book Gorillas In The Mist.’

I stayed at Bisate Lodge, which opened in 2017, a short drive away from the campus. A fire roared inside my thatched villa, which had a view from the hillside on to Bisoke volcano. A carved wooden gorilla at the door served as the “Do Not Disturb” sign.

I took a walk on the lodge’s nature trails in the afternoon, up to the 2 673m hilltop. Distant voices and the sound of drumming drifted up from the valley below as I circled around the edge of an old volcano crater. ‘One time, there was a gorilla around the crater,’ a ranger I met told me. ‘It came out of the national park and up onto the path here.’

The next morning, after a gorilla briefing at the park HQ in Kinigi, I set off for my trek with an armed ranger, hiking through farmland towards the park boundary. Soon after we’d crossed a wooden bridge over a volcanic rock wall to enter the forest, the gorillas made their abrupt arrival.

From Bisate Lodge, you gaze through a curtain of mist at two distant extinct volcanoes, Bisoke and Karisimbi.

For an hour, we followed the animals as they ate and moved in and out of thick greenery. The silverback stood upright to pull down high branches. An infant tried to do the same, imitating and learning. Seeing Marambo standing gave a clear view of his height and bulk – this is not a creature you’d want to wrestle.

Spending time with the gorillas was a peaceful experience. Babies climbed onto parents’ backs or heads. Juveniles stood and fed on plants, stripping bark with their teeth and fingers.

The family moved out of the forest onto more open land on the edge of farmland, spreading out around a mound of forest eucalyptus trees. ‘They like eucalyptus because it has sweeter sap and it has mineral salts that are good for them,’ Emmanuel said.

Later, looking back from where we parked our car, I watched as the gorillas sauntered across the open land at the foot of the volcano. Marambo was the last of them, his silver back clearly identifying him from a distance, as he walked into some bushes and was gone.

After another warm night at Bisate, I set out again the next morning, walking through local farms on the edge of Kinigi. Gorillas aren’t the only primates in Volcanoes. As we reached the edge of a forest, I saw golden monkeys darting around the hillside. ‘They like potatoes, so they like to come out of the park to find food,’ said guide Kwizera Diogene.

Once thought to be a subspecies of the blue monkey, golden monkeys have golden orange patches on their backs and upper flanks.

I made my way up for a closer look, watching and photographing the curious-looking monkeys as they paused to feed on hillside plants. It was a mellower experience than the gorillas, and far easier to keep up. ‘There are around 3 000 golden monkeys in the world,’ Kwizera said. ‘They’re an endemic species to the Albertine Rift Valley. They’re endangered, so we need to protect their habitat.’

The monkeys, with attractive orange and black coats, gradually moved from the farmland into the forest cover. Following them inside, we spent time among them as they fed on bamboo above us. ‘Unlike gorillas, for golden monkeys, the females are dominant,’ Kwizera said. ‘They’re territorial. In the mating season, males come from all over the park for a chance to mate with the females. After they mate, the females tell the young males they’re not wanted anymore, and they go.’

Leaving the still-feeding monkeys behind, we took the path back through the farms. Some of the local farmland is likely to be bought and turned back into forest. The Rwandan government plans to invest $255 million to expand Volcanoes National Park by about 23%, adding 37.4km². ‘The wildlife is expanding,’ Kwizera explained. ‘The number of gorillas is increasing. We need to increase food and space in the park, for more gorillas, more buffalo, more golden monkeys…’

Expanding the park would reduce conflict between people and animals, and create more jobs, a further boost to the local and national economy. It would also increase the area of habitat for gorillas, golden monkeys and other wildlife to thrive in, another step towards ensuring their survival. It’s likely Dian Fossey would be blown away by that, too.

Campus tour

Most of the funding for the campus was donated by Ellen DeGeneres, the globally recognised comedian and talk show host and her partner, actor Portia de Rossi, through their conservation non-profit The Ellen Fund. Built by MASS Design Group and covering more than 12 acres, the campus’s modern buildings were constructed using a grey, volcanic stone and other local materials.

For visitors, the Conservation Gallery is the focal point, with exhibition space and a 360-degree cinema, but there’s also a Research Centre, labs, offices and more. ‘The mission of the campus is to inspire a lifetime of conservation activities,’ Felix Ndagijimama said.

‘We’re raising awareness about the gorillas – the population has increased, but there are still threats. The labs we had before weren’t properly built – we’d just converted a kitchen in town. So now we have a Research Centre with proper labs, offices, computer rooms… We have an Education Centre. For many years, we’ve been training undergraduates from Rwanda University, and now we have student housing.’

Gorillas 101

Gorillas, the world’s largest primates, share around 98% of DNA with humans. They are capable of empathy and emotion, including grief – they’ve been observed mourning their loved ones.

Gorillas are vegetarians and eat up to 25kg per day – and they spend most of their day eating, mainly forest plants, such as eucalyptus. An average male mountain gorilla can weigh 180kg or more.

At night, they sleep in nests they build on the ground or in trees.

There are two species of gorilla: eastern and western. Mountain gorillas are a sub-species of the eastern gorilla.

According to the last census, there are 1 063 mountain gorillas in the world, living in Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC.

Critically endangered Grauer’s gorillas, also known as eastern lowland gorillas, are in a desperate plight in the DRC, the only country in which they’re found, with a decline in numbers of more than 60% in the last two decades.

Once in a lifetime

Trekking to spend time with mountain gorillas is the primary reason why travellers visit Volcanoes National Park. It’s not a cheap experience, with gorilla permits costing $1 500 per person in order to spend one hour with the gorillas.

Permits to see golden monkeys cost $100 per person, also for one hour with the animals.

Stay Here

Bisate Lodge

Bisate Lodge interior

Under the aegis of conservation groundbreakers Wilderness, these beautifully conceived forest villas are unlike anything you’ve ever seen, with a thrillingly imaginative design that takes inspiration from indigenous architectural practices – the interiors are spectacular, too.

Bisate consequently provides the most impressive accommodation anywhere in the vicinity of the rare and majestic mountain gorillas that live in Volcanoes National Park. Situated on a hill with views of the Bisoke, Karisimbi and Mikeno volcanoes, the focus is obviously on organised treks to one of the habituated gorilla families, but guests can also visit the “Twin Lakes” of Ruhondo and Burera and the lava tunnels of the Musanze Caves, take excursions to Iby’Iwacu cultural village, and trek to Dian Fossey’s original Karisoke Research Centre, located between Bisoke and Karisimbi volcanoes.

From $1 830 pps pn, including all meals

wildernessdestinations.com

Five Volcanoes Boutique Hotel

About midway between Kinigi and Ruhengeri, about half an hour from Volcanoes National Park, this comfortable, down-to-earth lodge has eight bedrooms, a family-size suite, and its three-bedroom Volcano Manor. There’s a restaurant and pool, and a number of activities arranged, including treks to see gorillas and golden monkeys, mountain bikes for hire, and canoe trips. Official rates start at $600 per night for a deluxe room, but you can score a much better deal (about 40% cheaper) by using a booking site such as Expedia or Booking.com.

fivevolcanoesrwanda.com

Kingi Guest House

If the thought of paying several hundred dollars a night fills you with fear, fear not: there is a cheaper, no frills option. Kinigi Guest House is easy on the wallet but don’t expect five stars. In fact, it’s more of a backpackers-type option, albeit one with cottages. It’s located perfectly, though, just a short stroll from the gorilla and monkey ranger headquarters where you start the treks. The rooms are small but the food is great, the views are amazing and the staff are really helpful and friendly.

Double rooms from $70 pn

insidevolcanoesnationalpark.com/kinigi-guest-house

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 print issue of Getaway

Words and photos: Graeme Green

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: 5 Eco-friendly getaways in South Africa

[ad_2]

Source link

Jarastyle – #Good #news #brink #extinction #Volcanoes #National #Park

Courtesy : https://www.getaway.co.za/travel-ideas/good-news-from-the-brink-of-extinction-in-volcanoes-national-park/